I have been publishing my views on construction and demolition waste since early 2000, when the matter was not in the public consciousness as much as it is now. Already then I identified the issue as a national problem requiring immediate action, let alone now, when excavations are going deeper than ever before.

Today, following recent discussions regarding land reclamation, certain crucial facts and considerations of fundamental importance are still not being addressed. Certain important decisions which might not immediately gain political points have to be taken, as the long-term effects of not doing so will have a severe impact on the environment, quality of life, tourism, and more importantly, the legacy we bequest to our future generations.

It is therefore imperative that this subject is debated between technical professionals and experienced people in this field. I would also like to share my views, as I have deepened my knowledge on the subject through 40 years of experience in the industry and following personal research.

Our shores and seascape cannot be compared to those in Dubai, Hong Kong, or others where the sea is relatively shallow and reclamation was carried out within existing sheltered harbours. Our surrounding sea is deep. Before simply dumping debris along our coastline, a breakwater, not simply a sea wall, must be constructed.

If we adopt an uninformed approach the effect would be that all dumped material would be washed away and spread all over the coastline as soon as there is a wind force of 7 or 8, which happens on an annual basis. This would spell disaster for all our sea flora and fauna at least for the surrounding five kilometres!

Our own history also teaches us valuable lessons. When construction waste was dumped in Balluta Bay, a relatively sheltered area, just after World War II, it was all washed away in a short time…

Another attempt at reclamation was made in Msida, which was retained. However, Msida is a very sheltered area and the water in that area of the harbour is very shallow. At the Freeport, which is open to the elements and where the sea is deep, the huge concrete quays were constructed only after the breakwater completed.

The country’s accumulated experience on the subject confirms without doubt the absolute requirement of having a breakwater to retain the material.

In the past we used to refer to this sort of waste as construction and demolition (C&D) waste. Today it’s referred to as Excavation and Demolition waste. Regardless of the nomenclature, the fact remains that 85 per cent of all this material is generated through excavation, the result of which is clean, inert material that can be utilised.

The demolition material, on the other hand, is contaminated with lime, paint, pieces of wood, steel and other contaminants. A degree of waste separation is possible, however, it is impossible to have it clean enough for sea use.

This means it is imperative that a decision is taken without any further delay to reserve the handful of disused quarries for the demolition waste, while finding a way to exploit the use of clean excavation waste for the benefit of the country.

The exact quantity is not known since a number of excavation contractors dump into their own quarries without it being recorded. However, it is estimated that, all in all, clean excavation waste amounts to three million tons per year.

The two disused quarries currently available will last around five years before filling up. Where will the three million tons per year of clean, inert excavation material be disposed of after that? I am sure no one would appreciate another Mount Magħtab next to their village!

There are solutions but these must be seriously discussed between all major stakeholders who must then take responsible and practical decisions. Any master plan must be considered for a period of at least 50 years.

Our shores and seascape cannot be compared to those in Dubai, Hong Kong or others where the sea is relatively shallow… Our surrounding sea is deep

So let’s look at the bigger picture and consider the relevant facts, as that is the only way of taking the right decisions while reusing Malta’s only raw material.

A breakwater of 15 to 20 metres in depth with five metres above sea level would cost around €70 million per kilometre. To hold excavation material generated over a period of, say, 20 years (equivalent to say 60 million tons), one would require a breakwater of a length of approximately five kilometres, at a total cost of €350 million!

The construction of the breakwater would take a minimum of five years before it is primed for the dumping of any material.

Let’s assume we could afford to finance this land reclamation… even if we did, such a high cost would render any development financially unfeasible.

Malta’s available lower coralline limestone (hardstone) used to produce the gravel for concrete is quickly diminishing, which means we have to import all the gravel, at a higher cost. Therefore, we should try to make use of this clean excavation material instead of hard stone gravel for non-structural uses.

On the other hand, the idea of reconstituted stone is definitely not financially feasible for building purposes. It would cost over 10 times more than a new stone block, and the volume needed is insignificant.

Here are some of my suggestions on how to use the material which could be considered:

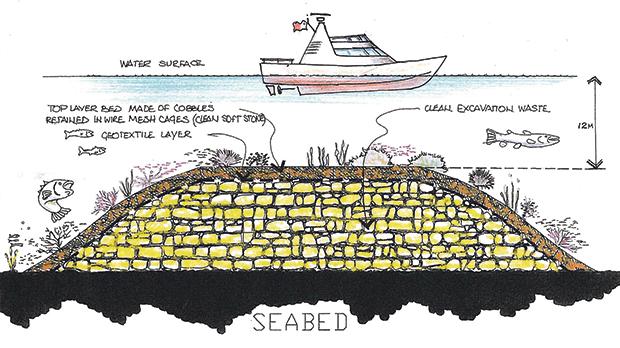

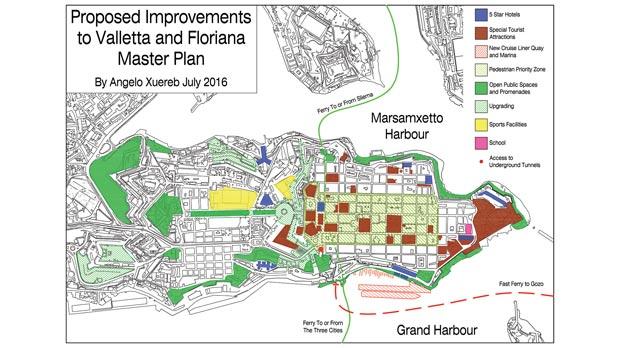

Create underwater artificial reefs (see figure 1) in selected areas, covered with sand and kilometres away from the coastline. Waves will not disturb material at 12 metres below sea level, and in order to protect this material from the lower currents these reefs can be secured with geo textile and large boulders or ‘tetrapots’ on their periphery. Once these reefs are closed off, this will create a habitat for various flora and fauna.

Create underwater breakwaters below 12 metres of sea level, located in certain open bays, but invisible from the landside. These will protect the erosion of our sandy beaches and possibly extend them. Construction methods would be the same utilised for the above mentioned artificial reefs. This will also create more shelter for boating and create the right conditions for flora and fauna.

Create tetrapots or quatropots (concrete blocks to support sea walls like those at Ċirkewwa). For the blocks below sea level these can consist of washed gravel from excavation waste, sand from lower coralline limestone, and cement. In order to achieve the required weight, these concrete blocks can be larger than those cast with lower coralline limestone (hardstone). These could also be used on a periphery of the underwater breakwater or artificial reefs mentioned above.

Create a large upmarket marina similar to Port Grimaud, in the south of France, where a marina for yachts is linked with luxury accommodation. Any reclamation must be contained in shallow areas within a bay, with concrete piles and a breakwater constructed before any material is disposed of between the contained areas.

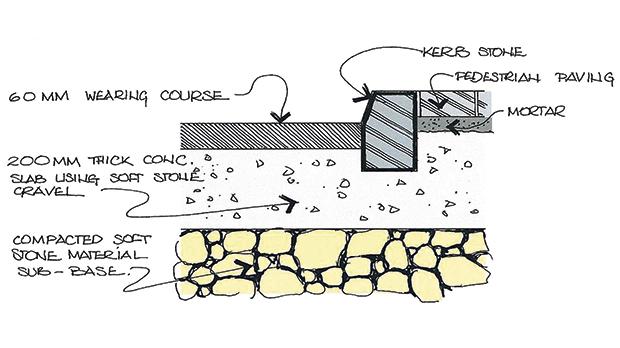

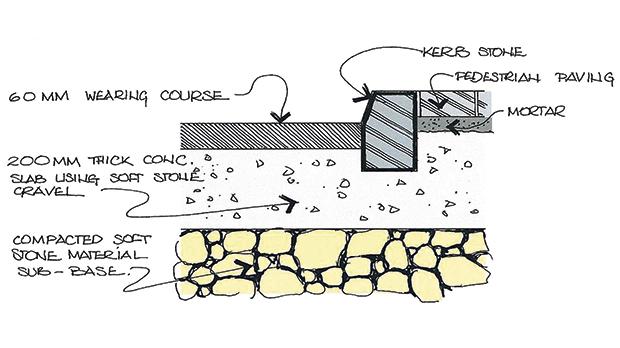

Use it for new road sub-base (see figure 2). Instead of a bitumen mix sub base we can use a thicker concrete base using washed excavation stone gravel with a slightly thicker final wearing bitumen course to guarantee tyre grip for a period of 10 years. The present lower bitumen base mix is not adequate since it is too soft. This makes the present imported good quality gravel and top wearing course recede to the lower level of the bitumen layer due to hot weather and heavy loads, with slippery road surfaces after just a few years.

Having studied this subject in depth I can definitely conclude the following:

• NO to land reclamation by the coast;

• NO to dumping of clean excavation material into disused quarries;

• YES to dumping of demolition waste into the few available disused quarries;

• YES to reusing Malta’s only raw material on large scale in the best possible manner;

• YES to the creation of artificial underwater reefs;

• YES to the creation of underwater breakwaters;

• YES to the reuse of excavation waste in road construction;

• YES for its reuse instead of lower coralline gravel hardstone for non-structural use;

• YES to the creation of up to three depots (one north, one south, one in Gozo) from where one can buy selected grades of stone for its reuse for different purposes.

The disposal of waste generated by construction activity is an acute national problem which we must resolve now. Not another second should be wasted, and a 50-year holistic plan has to be devised, as continuing to fire-fight the issue is no longer an option. I therefore strongly recommend the government appoints a professional and technical team to put forward a practical and feasible plan.

We certainly shouldn’t burden the next generation with acute problems that we should be able to solve ourselves today.